An hour or so later we were still gathered around the weird elixir.

Ahmat and I sat mired in our chairs with our matching red faces, more like brothers than ever, contemplating what we had done to ourselves. Two regretful wasps caught in resin. Rihangül and Aziz marveled at us the same way parents marvel at even the most deranged habits of their children. A worried line wriggled across Ahmat’s forehead. Another wriggled across mine.

I had experimented with my share of intoxicants. This one you had to reckon with. It made you question yourself, your life, decisions you had made, the truth of your relationships—it all kicked around in your mind.

I wanted more.

Colonel Aziz asked Rihangül if I liked the drink. He had interrupted me as I had been composing a brash argument in mumbled, pidgin English convincing them all I was as sharp as a tack. Aziz inched himself away from me. Was he afraid I would start a real fracas?

“Go tell the Colonel I don’t like it, but I like drinking it,” I said.

She tried to explain. I wasn’t convinced they understood. “And I like to drink it, because then it is gone!” I said. I slammed my glass on the table.

“Another one, brother Andrew?” Colonel Aziz inquired. He redirected the bottle’s glistening mouth at me.

“He’e,” I said. “Brother Andrew wants another one.”

Colonel Aziz poured it and blurted something out. “Aziz say he want to make another huge toast to Ahmat’s promotion andah to you too Andrew guy. They so happy to meet you andah you are they first American they have ever called they brother,” Rihangül said.

“I’m all for it,” I said.

We stiffened in our chairs for the “King of Toasts” and clanged our glasses together. “Hosh!” we exclaimed.

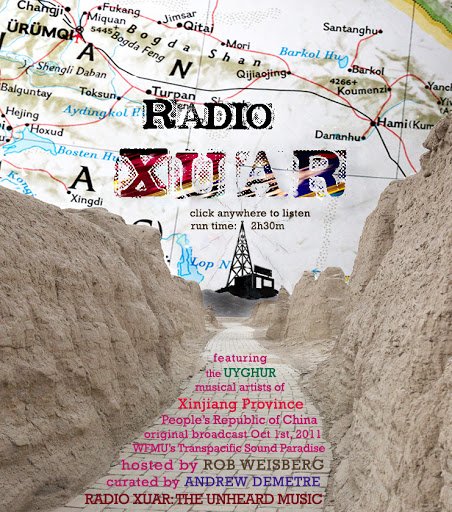

I hijacked the next toast. “To my brother Ahmat and his promotion to Xinjiang Provincial Postmaster General. To my brother Colonel Aziz and his sustained career in the People’s Liberation Army. To Rihangül and her safe return to her homeland. To Ürümqi and all the Uyghur people in Xinjiang. Hosh!”

“Woy my God,” said Rihangül. She covered her mouth again.

“Hosh! Hosh!” we said.

My aplomb brought on wild laughter and rapping knuckles. Our drinks sailed back. Ahmat inhaled his latest with such effort I thought he would fall out of his chair. He slammed his glass on the table, becoming aggressive, and emerged from his red-faced worry. He fleered at Colonel Aziz. Would I have to scrap with the new postmaster general now too?

Colonel Aziz smirked. His uneven chin reclined on the palm of his hand, his finger tapped his cheek. “Comrade Ahmat, where is your smile now? You smiled so much today. I have never seen you smile so much in your life. You must be tired of smiling. Smiling here, smiling there, smiling everywhere across Xinjiang. Now you will have no choice. You will always have to smile,” he said.

A thundering, stuttering, unreal, saved-up laugh blasted out the side of Aziz’s mouth. It hushed the room, then set off a chain reaction, as the Uyghurs and I shamelessly cracked up.

But Ahmat wasn’t finished. “Give me another. A double,” he said. Colonel Aziz tilted his forehead toward me for my approval. I gave it, and he refueled his friend. Ahmat inhaled his drink. Now a deep carmine rash spread across his face. He requested further drinks by merely lifting his index finger. Colonel Aziz always obliged him, and one after the next into Ahmat’s throat they went. Soon the polite man yanked off his silk tie and went haywire. His mouth revealed itself as the animated hole it was, as it gaped open like the maw of a doomed rat when he drank and puckered shut as if he had bitten into a lemon when he swallowed.

Suddenly a shellshocked stare overran his sunny gaze. His teeth protruded from his mouth. His tongue lolled, his hands clutched at the air, he hung off his bones, looking flammable. Gone was the charming composure. The slick-and-smooth new Xinjiang Postmaster General now sat gnashing his teeth. The djinn repellent had transformed him into a lobster-eyed, indolent galoot.

“Woy my God, Ahmat now too,” Rihangül said. She

ditched her frown behind her billowy sleeve.

“The new face of Xinjiang!” Aziz announced. His arms floated above his head, as if all of life’s ballast had dropped away. And like a python unhinges its jaw to devour prey larger than itself, Ahmat’s drunken smile devoured the room—a grinding, sodden, teary-eyed facebreaker whose afterimage persisting in my mind, appearing on-screen and off, here and there across the province, extolling the benevolent virtues of the People’s Post Office, dragged a broad smile onto my drunken face that was, still, no match for his.

The symptoms, and they were symptoms, waned. Colonel Aziz offered me another drink, but after witnessing how obliterated Ahmat had become, I declined. But he insisted—he couldn’t enjoy himself, so I would do it for him. There were countless ways to, but I couldn’t bring myself to say no. I acquiesced and proceeded to nonchalantly pour yet another drink into my mouth.

Like riding a bicycle or using chopsticks, once you learned how to “enjoy” the djinn repellent, you never forgot. There was only one way: cold disregard. Emotions and histrionics only made the process more excruciating. It reminded me of the mandatory and ritualized oral polio vaccinations I shivered through as a boy—exposed, no choice but to trust, imbibing a strange liquid. But in this case the ritual was taken to a willful and, thankfully, fully dressed extreme. A wavering morality of rudeness and gratitude between guest and host required you to weigh avoidance, revulsion, and suffering against pleasure, denial, and relief. And what pleasure doesn’t disguise a component of pain? To put it another way: I had become a connoisseur of the awful. And it didn’t matter how exotic or daring or dangerous it sounded at the beginning, the concoction, whatever it was, got you drunk. I was drunk in Ürümqi.

Then things took a turn. Ahmat’s dégringolade amid my swelling camaraderie with the Uyghurs erased any remaining delusions I harbored about having a go at Colonel Aziz. He had further gained my trust because he refused to drink and drive. And, I recalled, while he had had the nerve to strap himself in with a seat belt while we jaunted around in the mechanized scrum of Ürümqi, the rest of us surely didn’t. He wasn’t a loose cannon; he just looked like one. Behind his gnarly exterior, he reminded me of my mellow older brother, an infectious disease specialist I was certain to call for medical advice the next day. I was the looser cannon.

Colonel Aziz and Rihangül revved up another Uyghur conversation and discussed the possibility of Aziz securing a visa and traveling to America to check on his son, who, we were shocked to learn, was attending a prep school in Maine. Rihangül probed Colonel Aziz for answers. How did his son get out? All we could wheedle out of Colonel Aziz was that he had discovered a placement service run by a murky pyramid of Chinese agents who arranged visas and enrollment in private schools along the East Coast of the United States. The schools featured a primarily Turkish student body, and because Uyghur and Turkish are similar languages, it promised a segue into American life. He didn’t divulge any specifics or express much concern about his son’s exact whereabouts.

Any opportunities outside of the People’s Republic of China must be better than the ones in it, right? An education in free-for-all America could turn you into either a shining diamond or a freedom-pining, troublesome monster when you came back, if you came back. The PRC’s internal and overseas communication system—a temperamental faucet the government could turn on and off ensured Colonel Aziz could never reliably contact his son and, judging by the shrug of his shoulders, I assumed he had flat out given up.

Rihangül was lucky to have slipped through the emigration restrictions imposed on Chinese citizens, Muslim women, and Uyghur artists—she had escaped the wuˇ xˉıng hóng qí (the “Five Star Red Flag” of the People’s Republic of China), a patriarchal culture, and creative repression in one fell swoop. Her sort of luck was next to impossible. All I knew was that a distant relative had helped her secure an invitation letter to enter the United States and study English at a school in Queens. Rihangül’s nascent literary ambitions provided the perfect alibi. I was sure there was more to the story.

Then the stony PLA colonel, perhaps rendered fragile by the memory of his son, cracked. Through the cracks glinted the only light I had seen shine from him, and he began to regale us with visions of a dreamworld. A dreamworld I was certain existed in three bold colors: red, white, and blue. Where a person could walk right up to the front door of the White House to express a grievance and be invited in and greeted by the smiling Obamas, rather than being duped, dragged away in shackles, and thrown in prison. Where, simply by virtue of freedom itself, one could have all of one’s needs satisfied and even become a rich man. Where a man and a woman could procreate at will, raising as many children as they pleased. A dreamworld without intrusive government controls or interference. Where raising a bountiful family of emancipated children would be highly incentivized, and where each rising generation of that family would do the same and enjoy even greater privileges than the last.

This policy of family rearing was a far cry from that of Xinjiang,

where such freedoms might never be won.

As Colonel Aziz spun out his utopian dream like so many strands of colored silk, the melodious drone of his voice sent my mind wandering into a landscape, a newly alien land of plenty: America. The boring suburb of concepts transformed into the most exotic place I could imagine. Shining, glorious freedom sat just on the other side of the earth, a scant twelve hours away, across the lower rim of the Arctic Circle. One day Aziz might walk into it with his wife and family. He would take a stroll in one of the many New York Cities dotting America, each one filled with blithe, sashaying, starry-eyed, free citizens who had all of their needs and expectations met, whose sole burden was the weight of unlimited potential.

Then Rihangül and brother Ahmat joined in. My brain still tried to make sense of their sonorous buzz: the trills, the rolled r’s, the ululations, a comforting sound like talking sand, the üp’s and the kha’s, the sublimely urgent cadence as resonant and dreamlike as an ensemble of cicadas, distant hammers, desert winds, cellos, and songbirds. What the three of them were saying or what images they were conjuring, I didn’t know. Judging by the noisy fun being delivered up, it was easy to infer that the other two were adding to the growing skyline of Aziz’s utopian, far-off Western dreamworld. Demolitions might have been occurring as well.

I found the energy to make my own contribution to their fantasy. Dreamworld Aziz needed one improvement—a system of credit whereby anyone could get something for nothing: automobiles, homes, children’s toys, any iThing you wanted, the month’s food, advanced education, car and health insurance, even emergency medical attention. Heck, go out and get hurt, you’re covered!

In the streets of Ürümqi, as in wider China, cash was king. Everyone packed fistfuls of folded-over, baguette-thick rolls of Chinese currency. Hell, I did too, ever since I had become a living, breathing extension of Rihangül’s purse—her designated cash mule—upon our last visit to the black money- market thriving on the very steps of the downtown Ürümqi branch of the Bank of China. A fat, coal-soot-and-god-knows-what-else-covered worn wad of red yuan was stuffed in my jacket’s internal pocket at that very moment. It was reassuring, even thrilling, to have it there—as reassuring and thrilling as discovering you had a backup heart. Had someone seen me in my Manhattan neighborhood, pockets bulging with cash, I would have been mistaken for a baller!

I begged Rihangül to translate a system of credit into their brainstorm. She began to, but I couldn’t muzzle myself anymore, and I recklessly blurted out the idea in English, their certain lack of comprehension be damned. Rihangül waved her hands across my mouth trying to shut me up; I swatted her hands away in order to continue. We must have looked insane to them.

I slipped a credit card out and placed it on the table in a dreary patch of light. Ahmat and Aziz fell silent. The something-for-nothing card, a plastic miracle available in silver, gold, platinum, or any other color you so desired. I explained to these denizens of the ultimate cash economy how one thin plastic card, tattooed with numbers, could contain such streamlined power. It could almost bring you back from the dead. Who needed cash?

Aziz and Ahmat picked up the card and took turns holding it as gingerly as they might hold the hair of a baby. What was the function of all the numbers? I couldn’t explain how it worked, only that it did. My credit card was the perfect machine. My confident articulation of the word machine drew smiles out of them, because machine is the word for car in Xinjiang. It’s not used for any other machine—exclusively for the automobile. I had been insisting my credit card was the perfect car. Machine is one of a handful of Uyghur words having remotely the same meaning in English. Another is man, which means I.

They handed back my credit card and stared at me with nonplussed indifference. I wiped the card off the table and unleashed a wide, depraved yawn. Ideas still churned in Aziz’s eyes, and I swear the Stars and Stripes overcame his irises, waving gloriously in some imaginary wind. He spoke in that elegiac way they do here: an aura of politeness forming, eyes bright and animated, gaze unfocused, tongue adept, leaving the listener wondering if he is the one being addressed at all.

I didn’t comprehend a word of what he said. My ears had surrendered, and I had become effectively deaf, so I could only watch. But I wanted to stay awake—the polite thing to do—so I focused on their lips as they stretched into radiant smiles and puckered around umlauts like so many kisses. To them it was everyday speech, this Uyghur language. To me it was poetry, a poetry that had corraded me into submission. Soon my eyes and ears retreated to their own private rooms. . .